The key to happiness lies with porcupines.

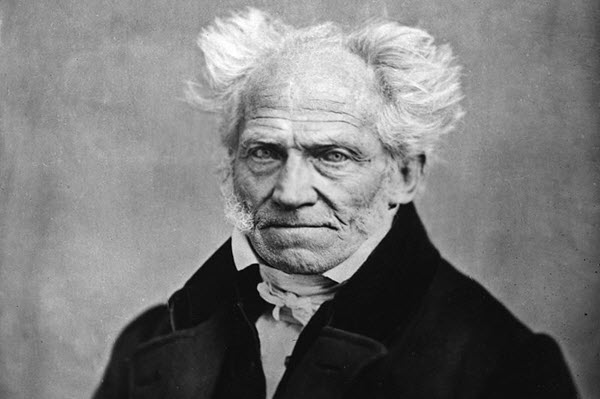

Strange as it sounds, it’s an idea that was first articulated by Arthur Schopenhauer. He’s a brilliant philosopher and pessimist of epic proportions.

Schopenhauer might not be the first person you’d normally turn to for well-being advice. This is because of him, all human actions were essentially worthless. He maintained that romance was an exquisite delusion. Women were overgrown and mindless children and marriage were things that required one to be “blindfolded into a sack hoping to find out an eel out of an assembly of snakes”.

Needless to say, Schopenhauer was single.

But despite his pessimism, he had a keen awareness of the intricacies of relationships or the problems that they can create. While he took a famously bleak attitude toward the future of humanity, Schopenhauer did suggest that there is one – and only one – key to happiness.

Why We’re All Porcupines

Schopenhauer believed that human beings had an aversion to closeness and were generally uncomfortable with their own emotions. To demonstrate his theory, he put forth a simple parable:

You’re a porcupine. It’s cold out. To stay warm, you need to huddle next to other porcupines, in close physical proximity. But, the moment you are suitably close to another porcupine, you are pricked by his sharp spines. So, you move away where no one can touch you.

Then, of course, you realize that it’s still cold and you’re beginning to freeze. You come back together with your fellow porcupines, holler out in pain at the sharp spines, and retreat again. And so goes the endless dance of human interaction: isolation, intimacy, retreat.

The process will continue, Schopenhauer said, until all the porcupines reach a state of equilibrium, in which they discover “a mean distance at which they [can] most tolerably exist”.

No one is entirely alone, but everyone is still fundamentally isolated. Porcupines, like humans, will always be “mutually repelled by the many prickly and disagreeable qualities of their nature”.

However, while Schopenhauer may have set out to illustrate that humans can never be perfectly compatible with each other, his porcupine parable shows how strangely fragile isolation can actually be. Even people who choose to be alone will still naturally gravitate toward each other. Humans, across time and cultures, will always seek intimacy.

Are we doomed?

Unfortunately, Schopenhauer had little to offer by way of a remedy for the porcupine dilemma—perhaps because he believed that “misfortune, in general, is the rule”. The only way to assuage one’s isolation, he said, was to cultivate an “inner” warmth.

In other words, if you generate your own source of heat, you can survive at a safe distance from other people.

While Schopenhauer did not elaborate on his theory of ‘inner warmth’, it’s not difficult to infer a modern (and less morbid) takeaway: it is impossible to rely entirely on another person to give you everything you want.

Being happy with someone else means being independent, self-sufficient, and content on your own first. This doesn’t mean shutting yourself off from the rest of the world. Instead, it’s cultivating the inner strength to face the rest of the world.

Compassion and Love: The Secret to Happiness

While Schopenhauer didn’t resolve the porcupine problem directly, another one of his theories provides an adequate solution. On The Basis of Morality (1839), his major work on ethics, he argued that only one force can free the soul and relieve our pain: morality.

More specifically, compassion.

According to Schopenhauer, all human happiness, satisfaction, and well-being lies in “the everyday phenomenon of compassion,…the immediate participation, independent of all ulterior considerations, primarily in the suffering of another, and thus in the prevention or elimination of it”.

Without compassion, we view each other as distinct individuals, alien and separate. Compassion, on the other hand, requires us to recognize that another’s suffering is exactly the same as our own. A compassionate person directly feels another person’s life. It is a sense that transcends physical distance and our own isolation. It allows us to connect with someone in a way that defies all cognitive reason.

What does this mean for our porcupine friends? While there may be an inherent limit to the amount of physical closeness we can achieve, there is no limit to what our minds and emotions can do to bridge the gap between us. Compassion is responsible for the ultimate paradox: feeling a greater intimacy from a distance that we would feel by standing side by side. Compassion and love are indeed essential to each other.

In the end, it is compassion that will allow us to experience the entire range of human emotions. That includes– sorry, Schopenhauer – optimism.